In the year 1908 Owens Valley residents had already been riding the Carson and Colorado Railroad for nearly 25 years. But now grumbling began to surface from a frustrated population; the train was on the wrong side of the Valley. The railroad was built specifically to serve mining operations on the eastside, but the population centers were to the west. Residents wanted a railroad connecting their towns, and they were ready to make it happen.

A headline in the September 1908 edition of the Big Pine Herald announced “BIG PINE HAS A DEPOT SITE FOR RAILROAD: Free Right-of-Way Movement Gains Immediate Support.” Local resident J.H Coe was quoted as saying, “there is nothing of greater importance to the people of the west side of this valley than the building of a standard gauge [railroad] on this side.” He and others offered free land to Southern Pacific for right-of-ways, but it went nowhere. A few years later, some enterprising men attempted to capitalize on this longing.

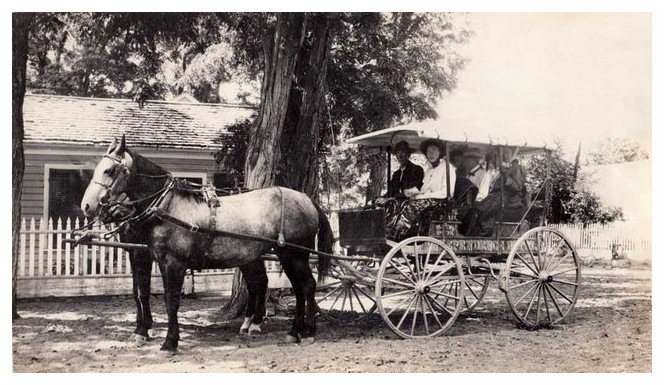

Since 1883, to catch a ride on the Carson and Colorado, travelers from Bishop had to endure a horse and buggy ride across four miles of bumpy, dusty dirt roads to get to Laws Depot. Some trips could take over an hour; and later, early automobile drivers did their best to avoid flat tires. When residents smelled rain in the air, it could be a muddy trip as well.

Since 1883, to catch a ride on the Carson and Colorado, travelers from Bishop had to endure a horse and buggy ride across four miles of bumpy, dusty dirt roads to get to Laws Depot. Some trips could take over an hour; and later, early automobile drivers did their best to avoid flat tires. When residents smelled rain in the air, it could be a muddy trip as well.

After nearly thirty years, Bishop was ready to join the modern world or transportation. Three men stepped forward and proposed a railroad between Bishop and Laws Depot. But first they had to visit a man in Nebraska.

In 1910 one of the three men, Charles Johnson, traveled to South Omaha, Nebraska to meet one C. Carey to secure a railroad franchise. This would lay out the state and federal ground rules for the construction and operation of a railroad. They successfully secured the franchise. But that was it, nothing else happened, and plans to move forward never materialized. However, someone else was waiting

in-the-wings.

Later that year, according to The San Francisco Call newspaper, “Articles of incorporation of the ‘Owens River Valley electric railway company’ formed to construct and operate a railroad in the Owens River valley...the company is capitalized at $200,000.” That number represents a potential company income of $4 million in today’s dollars. With that news, Charles Johnson decided to turn over his railroad franchise to the two men who started the company, who in turn began to initiate their grand plan.

The Owens River Valley Electric Railway Company’s president was Harry Shaw who, according to the book Railroads of Nevada and Eastern California, “was also president of the Owen Valley Bank, veteran of a full seven months banking operations.” Shaw’s inferred lack of banking experience, combined with some creative stock incentives, made for a colorful episode in Bishop’s history.

Their plan was for a four and a half-mile railroad, actually an electric trolley, between Bishop and Laws. As railways went, it was an unimpressive distance; so for credibility, plans for a twelve mile connection was added from Bishop to Round Valley, along with a sixteen mile connection from Bishop to Big Pine. But Laws was their main goal. The next step was raising cash, and they were banking on the temptation of apples.

Offices were opened in Bishop in early 1911 and a full-page page advertisement was placed in the Inyo Register promoting their plan and offering stock in the company, which included a “bonus” stock. H.N Beard, the company general manager, had his eye on an agricultural investment: the “bonus” stock was for a 1,300 acre apple orchard, nearly two square miles in size.

This stock incentive was detailed in the company’s promotional booklet titled “The Big Red Apple – The Money Tree.” Soon local wags, the jokesters of the time, tossed out a nickname for the new railway, “The Red Apple Route.” The name stuck and word was out.

Residents woke up to a stack of headlines in the February 9, 1911 edition of the Inyo Register: “BIG DEVELOPMENT ENTERPRISES: Preliminary Surveys for Bishop and Laws Electric Railway to Begin This Month and Construction to Begin by Midsummer,” “IMPROVEMENT AND COLONIZATION BY A MILLION-DOLLAR COMPANY: Over Two Hundred Thousand Dollar Investment in Orchard Land is Highest Mark Yet Reached in Inyo County record.”

The story revealed the company’s directors were “San Franciscans,” but promised local control of the company as “additional stock will be sold to outside buyers only after the local people have majority control.” They insisted that local directors would soon be chosen only from of a list of prominent locals. Name dropping of current stockholders included Bulpitt, Watterson, Schober, and Gerkin.

As for the record breaking orchard land investment, the register stated, “First payments on purchase...will be made on over 2,000 acres of Sunland district land within one week.” It had yet to be purchased. Regardless, work began on the Red Apple Route.

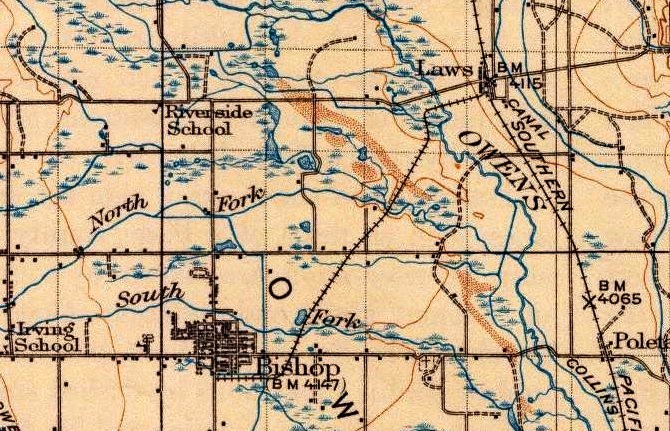

By late March 1911, the Owens River Valley Electric Railway Company had completed surveying the railway. The Red Apple Route would run four and a half miles from Laws Depot, across the Owens River, travel southwest past the northern end of today’s airport, cross the East Line Street canal near Hanby, and connect to Bishop’s South Main Street at what is now High County Lumber. With the survey complete, grading was next; but first, the festivities.

On a Saturday morning, June 16, 1911, stores on Main Street closed for a two-hour parade celebrating the beginning of construction of the Red Apple Route. Twenty-five horseless carriages paraded down Main St., but the planned musical entertainment failed to materialize. The celebration included long and passionate orations expounding the many benefits of the railway. Within the copious, colorful proclamations was a loosely stated claim that enough stock had been sold in the Company to build the electric railway. Indeed, construction began the following Monday.

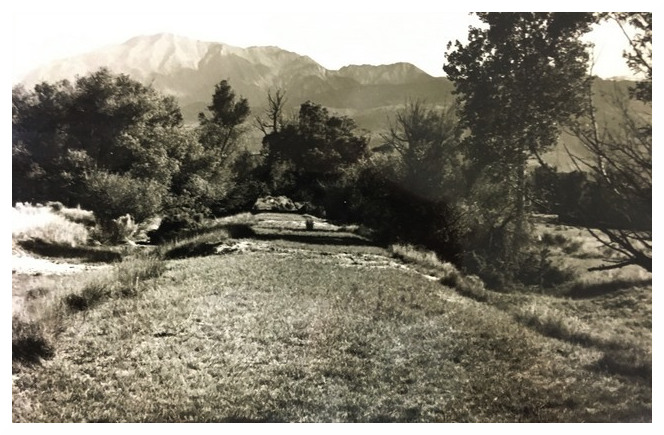

Thirty-two men and sixty horses began work on a major month-long cut-and-fill on the Owen River’s edge near Laws. After that, the rest of The Red Apple Route construction was a simple raised berm along level ground. For the crossing of creeks and swamps, the Carson and Colorado delivered four railroad cars filled with pipe for the thirty-nine culverts along the route. Next came wood for fencing and possible ties, for that they needed a lumber mill.

Thirty-two men and sixty horses began work on a major month-long cut-and-fill on the Owen River’s edge near Laws. After that, the rest of The Red Apple Route construction was a simple raised berm along level ground. For the crossing of creeks and swamps, the Carson and Colorado delivered four railroad cars filled with pipe for the thirty-nine culverts along the route. Next came wood for fencing and possible ties, for that they needed a lumber mill.

The Electric Railway Company purchased land in upper Black Canyon SE of Bishop in the southern most portion of the White Mountains to build a sawmill. The lumber would be cut from trees from the top of the White Mountains, reportedly including bristlecone pine.

By early August, the grading, culverts, and sawmill were complete. At month’s end, the berm was ready for railroad ties, rails, and fencing. Then things began to faultier.

The Black Canyon sawmill was not living up to expectations. Frequent disruptions in cutting logs delayed the fencing along the right-of-way. Rumors were circulating that the company would use a gas powered engine instead of the proposed electric train which would rely on relatively new electric power. But the company insisted they would stick with the original plan. Work halted in November of 1911, but they assured work would pick up after winter.

Winter of 1912 came and went with no sign of work on the Red Apple Route. Spring came and went, and still no progress. Finally in the June 20th edition of the Inyo Register, one day before the official start of summer, Owens River Valley Electric Railway Company president Harry Shaw declared in a brief story titled Action Expected that “large plans are maturing, looking to work on the road in the near future.” The future never arrived.

With the City of Los Angeles purchasing land and water rights to fill its new aqueduct, the downward spiral of the Valley’s agricultural economy finally reached Bishop. Investor confidence in the apple orchard, and accompanying railway diminished, and the company silently faded away. However, the dream of a railway did not completely die.

In the early 2000s, locals came together to form a company for the purpose of finishing what was started nearly 100 years earlier. Volunteers of the newly formed Owens Valley Railway Company tirelessly raised funds and gathered railroad artifacts to build the Red Apple Route. Train tracks were gathered from around the region and amassed at Laws. A vintage wooden bridge from the abandoned Carson and Colorado railroad was found, disassembled, and brought to Laws to be reassembled over the Owens River. Government funds were acquired to develop an environmental review and plans for the construction of the railway.But community fundraisers and momentum wasn’t enough. Many factors, including the railway’s crossing of LADWP land, made the dream unattainable. Once again, the dream died and all that remains is the railroad grade, and a 1913 topo map showing what could have been.

(Images courtesy of Laws Railroad Museum & Historical Site, Eastern California Museum, & Ted Williams)

Copyright © 2017 Ted Williams. All Rights Reserved